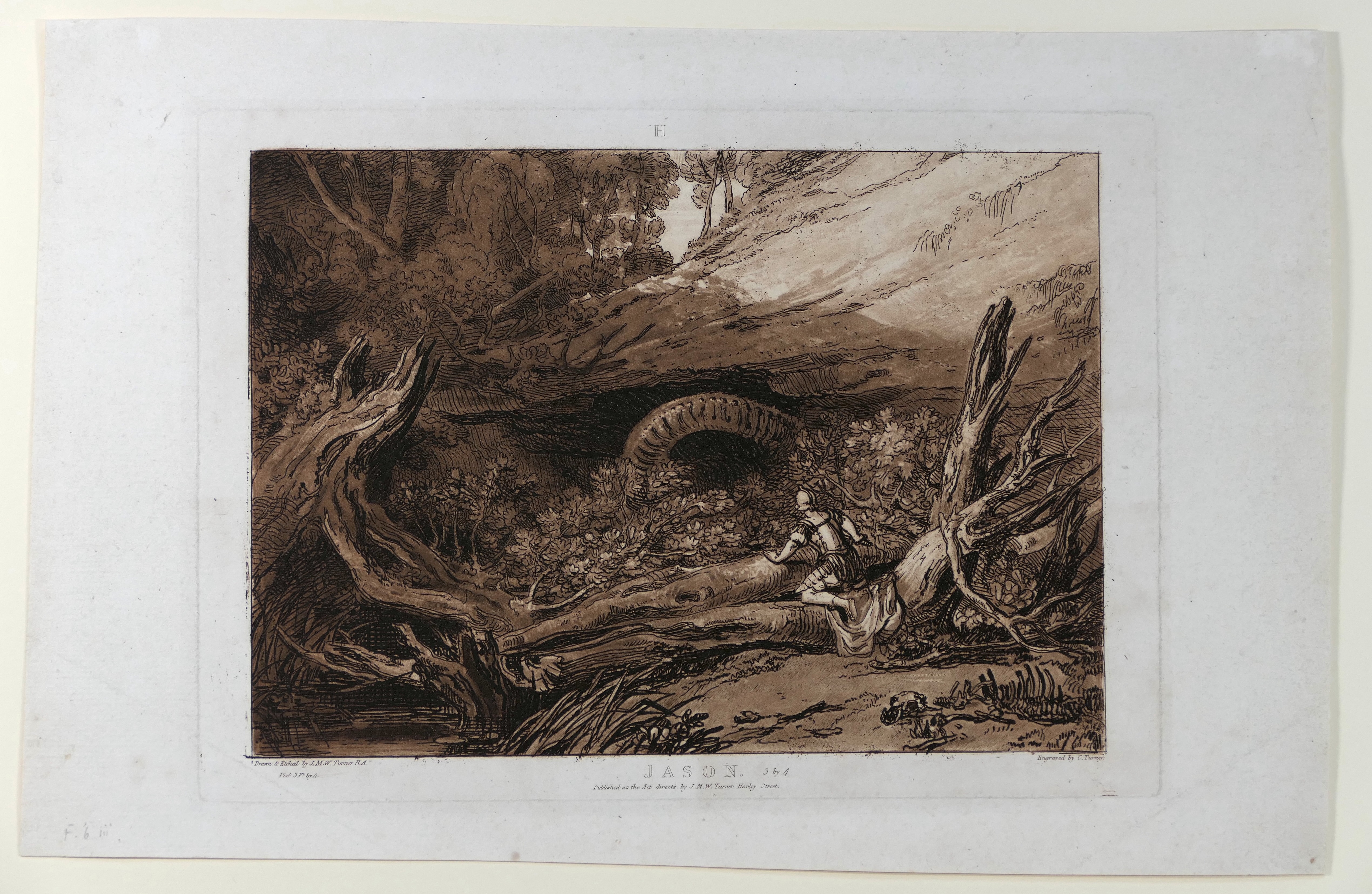

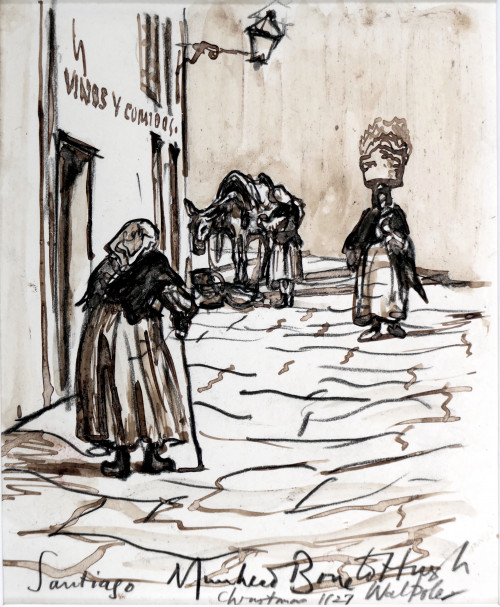

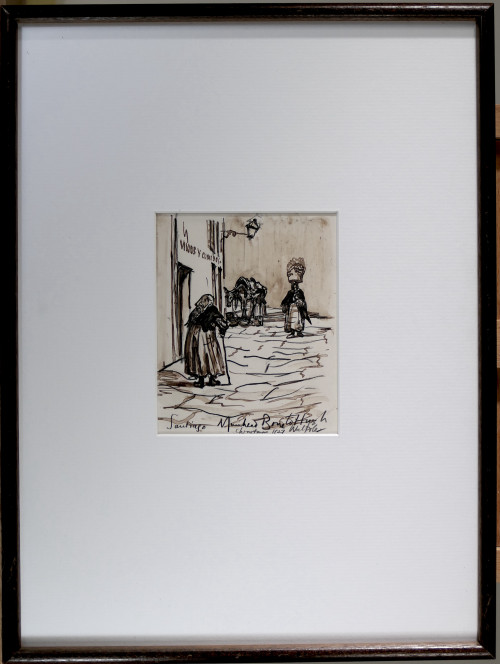

Jason (unique Engraver's Proof iia)

Jason (unique Engraver's Proof iia)

James Mallord William Turner RA

1210

This Engraver’s Proof of ‘Jason’ - almost certainly unique - was made by J M W Turner with his friend, the mezzotint engraver Charles Turner, to be one of the seven subjects in the first part of the artist’s ‘Liber Studiorum’, the unfinished series of prints he published from 1807 onwards to place his major pictures in their proper classifications, or 'departments' of art as Andrew Wilton describes them in 'Turner and the Sublime'. The purpose of this printer's proof would have been to establish how close the mezzotint engraver, Charles Turner (no relation, but a fellow student at the Royal Academy Schools) was getting, with his mezzotint additions to the artist’s etching, to the final effect that the artist sought. The proof, made with dark brown ink, beautifully displays Turner's crisp etched lines and the high contrasts he was seeking to add drama to the scene.

Turner based an initial sepia watercolour design of ‘Jason’, and consequently this print, on a painting he showed at the Royal Academy in 1802, titled 'Jason, from Ovid's Metamorphosis'. Although a mythological subject, Turner had his friend letter it ‘H’ for Historical, being the earliest work in this classification made for the 'Liber Studiorum'. In his 1924 ‘Catalogue Raisonné’ of the Liber project, the successor of W G Rawlinson’s 1878 'Turner's Liber Studiorum, a description and a catalogue', A. J. Finberg lists 91 plates, of which many were produced in multiple states. Turner was meticulous in the development of the prints and demanding of his collaborators, usually etching the plates himself then poring over the Engraver's Proofs (as Finberg describes them), and continually altering them in search of perfection. The soft copper plates did not produce many fine images, reportedly wearing out after twenty to thirty prints were taken, and therefore had to be regularly re-engraved to keep up the quality Turner demanded. There are therefore numerous states and proofs of Liber plates in existence.

Although it has been annotated in pencil in the margin 'F.6.iii', indicating that it is Finberg's third state of this print, which also accords with Rawlinson's third state, it is in fact a perhaps unique Engraver's Proof (to use Finberg's terminology) recording the transition from the second state (ii) to the third (iii). We should probably therefore label it iia. Indeed, there is a letter 'A' written in pencil in what may be a contemporary hand - possibley of the engraver or printer - on the back of fthe proof at the edge of the plate (visible in photographs). Also on the back of the sheet, in the top left corner are some pencil marks that look like they may be numbers, perhaps the second one a '3". If so, they are perhaps reminiscent of the shape of numbers in Turner's Liber notes sketchbooks.

In his progress to the third state the engraver had re-positioned and made the ‘H’ smaller, amended the lettering below the image and adds the dimensions of the oil painting, as well as carrying out Turner’s instructions for changes to the images. Having pulled this proof it was clearly decided to include more highlights in the foreground, which are to be seen in state iii. The proof is thus significant in helping reveal the working processes of the artist and engraver, feeling their way to the third state for publication. The paper used, which Turner chose as the best available for the etching and mezzotint processes, was Dovecote watermarked Auvergne 1742 laid paper made by the French mill of T. Dupuy (see photograph). The paper has been cut on slant beneath the plate mark, indication the sheet used was an off cut for proofing purpose rather than publication. and probably unique. Certainly, no other example of this state has yet been identified in museum collections. As such it is an interesting illustration of how artist and engraver worked together on one of the most significant of the early Liber plates, to achieve the finished print for publication.

Rawlinson writes, "The Etching of this plate is exceedingly fine, and is carried further perhaps than any of the others. Mr. Ruskin, in the Elements of Drawing (p. 134), includes it among those most desirable for study. He has also alluded to the plate in various passages in Modern Painters. In vol. iii. p. 324, classing it among the live or six finest subjects of the Liber, he pronounces it as, with them, “ founded first on nature, but modified by fond (the italics are his) imitation of Titian.” In his chapter on “ Imagination Penetrative ” (J/. P. vol. ii. p. 16G), contrasting the treatment by Retsch of a similar subject (illustrations to Schiller’s Kampf mit den Drachm) with Turner’s here, he finely says : —

Take up Turner’s Jason, Liber Studiorum, and observe how the imagination can concentrate all this and infinitely more, into one moment. No far forest country, no secret paths, nor cloven hills ; nothing but a gleam of pale horizontal sky, that broods over pleasant places far away, and sends in, through the wild overgrowth of the thicket, a ray of broken daylight into the hopeless pit. No flaunting plumes nor brandished lances, but stern purpose in the turn of the crestless helmet, visible victory in the drawing back of the prepared right arm behind the steady point. No more claws, nor teeth, nor manes, nor stinging tails. We have the dragon, like everything else, by the middle. We need see no more of him. All his horror is in that fearful, slow, griding upheaval of the single coil. Spark after spark of it, ring after ring, is sliding into the light, the slow glitter steals along him step by step, broader and broader, a lighting of funeral lamps one by one, quicker and quicker ; a moment more, and he is out upon us, all crash and blaze, among those broken trunks; — but he will be nothing then to what he is now… Now observe in this work of Turner that the whole value of it depends upon the character of curve assumed by the serpent’s body ; for had it been a mere semicircle, or gone down in a series of smaller coils, it would have been, in the first case, ridiculous, as unlike a serpent, or, in the second, disgusting, nothing more than an exaggerated viper ; but it is that coming straight at the right hand which suggests the drawing forth of an enormous weight, and gives the bent part its springing look, that frightens us. Again, remove the light trunk on the left, and observe how useless all the gloom of the picture would have been, if this trunk had not given it depth and hollowness. Finally and chiefly, observe that the painter is not satisfied even with all the suggestiveness thus obtained, but to make sure of us, and force us, whether we will or not, to walk his way, and not ours, the trunks of the trees on the right are all cloven into yawning and writhing heads and bodies, and alive with dragon energy all about us ; note especially the nearest with its gaping jaws and claw-like branch at the seeming shoulder ; a kind of suggestion which in itself is not imaginative, but merely fanciful (using the term fancy in that third sense not yet explained, corresponding to the third office of imagination) ; but it is imaginative in its present use and application, for the painter addresses thereby that morbid and fearful condition of mind which he has endeavoured to excite in the spectator, and which in reality would have seen in every trunk and bough, as it penetrated into the deeper thicket, the object of its terror.”

Dimensions:

1807

Etching and mezzotint on T. Dupuy 'Auvergne 1742' laid paper, watermarked with the lower part of a Dovecote watermark, not recorded in Finberg.

Inscribed "A' in a contemporary hand verso. Fulll lettering of the published plate recto.

RELATED ITEMS